Have you heard of Alvira? Once a growing community in Central Pennsylvania, the land was taken over by the government during World War II. In this episode, Ethan and Holly are talking about this lost village, the ways it’s residents were affected, and what the government wanted with it.

Listen here: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/remembering-alvira-a-village-lost/id1673471716?i=1000613932892

Alvira, a Village Lost

December 7, 1941, was an infamous date that not only launched US involvement in WWII, but also defined the beginning of the end for the Central PA town of Alvira, and the lives the people of that community had known.

Unlike the war, Alvira’s ending would be swift and almost unnoticed…. which was exactly the way the US government wanted it to be. They knew that on the evening of March 7, 1942, at the Stone Church in Alvira, a promise had been made to the residents that the US government would sell back the property taken from residents by eminent domain for the War Department’s use. And the government knew that promise would be broken.

History:

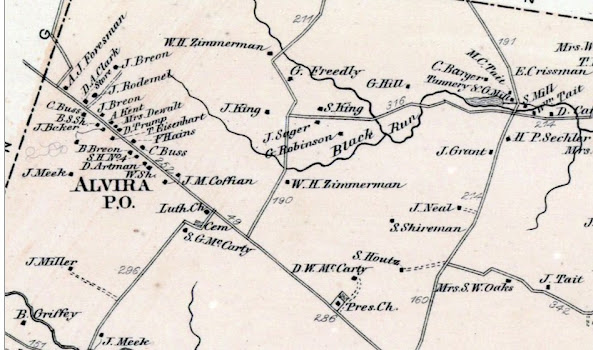

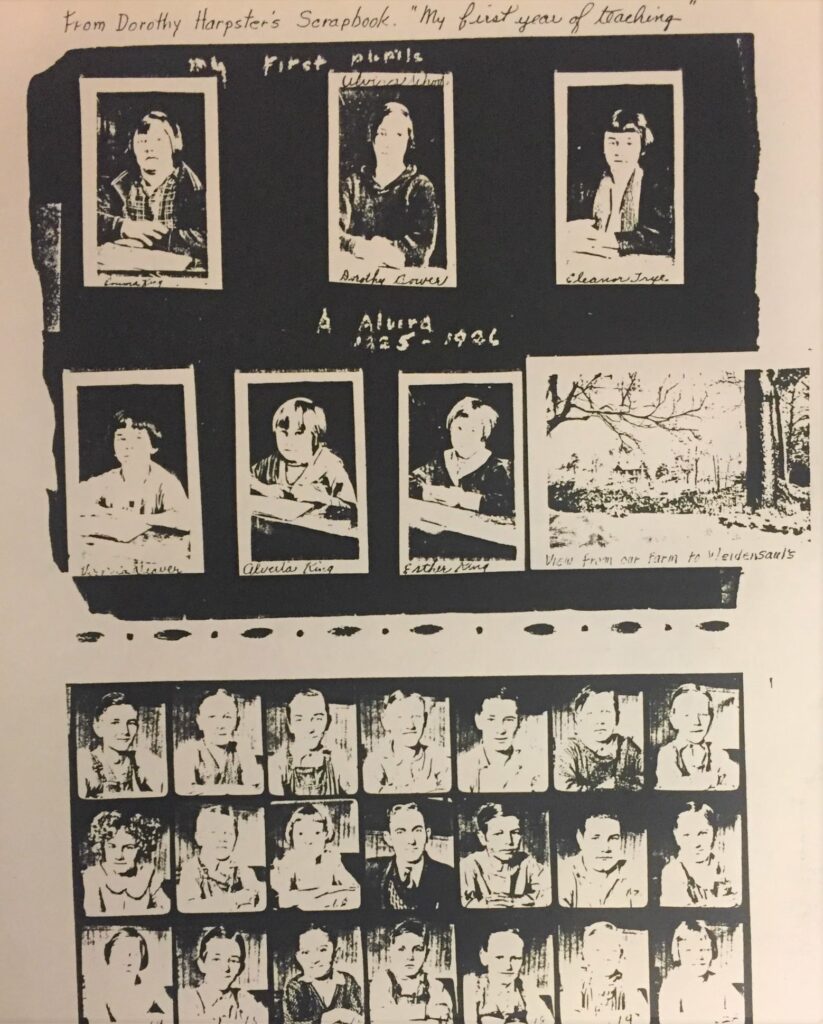

For over 200 years the Culbertson Trail, now known as Alvira Road, connected Allenwood with Elimsport and the rest of the White Deer Valley. As it passed through the village of Alvira (originally founded as Wisetown in 1825), homes, churches, businesses, and a school graced the sides of the street.

Until the close of 1941, and for at least 100 years before that, landowners in Alvira and the surrounding area owned thousands of acres of prime farmland that they faithfully tended, and that served them well. Alvira was a flourishing community until the federal government condemned, “purchased,” and took by eminent domain the properties from their owners in the summer of 1942 so that their entire town could be leveled and turned into a TNT manufacturing plant and storage facility known as the Pennsylvania Ordnance Works (POW).

But just 11 months after the Pennsylvania Ordnance Works started manufacturing TNT, it was closed due to a lack of need for the TNT being made and stored there.

And while the residents had been promised that they could buy back their land after the war, that promise was broken. The federal government instead kept the land and gradually divvied it up.

Today only crumbling foundations hidden beneath thickets and choked by foliage remain – ghosts of what had flourished before.

In the 95 years of its existence, Christ Lutheran Church, lovingly nicknamed the Stone Church, had come to symbolize the Alvira community’s spirit, sacrifice, and strength. The church was the community meeting place, and a haven for villagers during the Civil War, World War I, the Great Depression, and the recent attack on Pearl Harbor, which ignited WWII. The loyal citizens of Alvira rallied behind scrap metal and tire drives. They rationed gasoline, butter, and silk, embracing the same spirit of sacrifice they had practiced in the not-so-distant past. But even the most supportive of war efforts could not have imagined the level of sacrifice that would be demanded of them.

Over 300 people attended the first meeting at the Stone Church on Monday, February 16, 1942. The purpose was clear – to oppose the increasingly loud rumor that had been circulating since December,

A petition was filed by the government in March of 1942 in the federal courthouse in Scranton, seeking the right of immediate condemnation of 7,604 acres of the White Deer Valley, and possession of all properties within the Ordnance Works as well as other properties outside of the Ordnance fences. The petition was granted almost immediately.

On March 7, 1942, the War Department played its hand. Over 400 angry residents attended the second Stone Church meeting, where the fate of their town was announced. At this time, Mr. Walter E. Sherwood, regional manager for the Real Estate Branch of the War Department told residents that at least 50 properties would be confiscated. No information regarding the boundaries of the land that would be taken or the purpose for which it would be used could be given.

In reality, the War Department had conducted a charade at the Stone Church. Prior to March of 1942, Stone & Webster, the general contractor, had been awarded a $15 million dollar contract by the federal government, and the U.S. Rubber Co. was awarded a War Department contract to operate a TNT plant in Central PA. By the time of the groundbreaking for the POW, on April 14, 1942, Alvira was already gone. Over 200 properties on 8,500 acres had been seized by the government.

On April 22, 1942, the Montgomery Mirror reported that Colonel T.C. Gerber, Commanding Officer of the POW, promised that “every effort will be made to retain intact improvements such as buildings, barns, and live trees…. Should the land be resold, it might be that many families will return to their homes and again use this land for farming.” His final statements about the POW after it’s purpose was released were that “no loading of projectiles or bombs will be done in this vicinity.”

The Exodus:

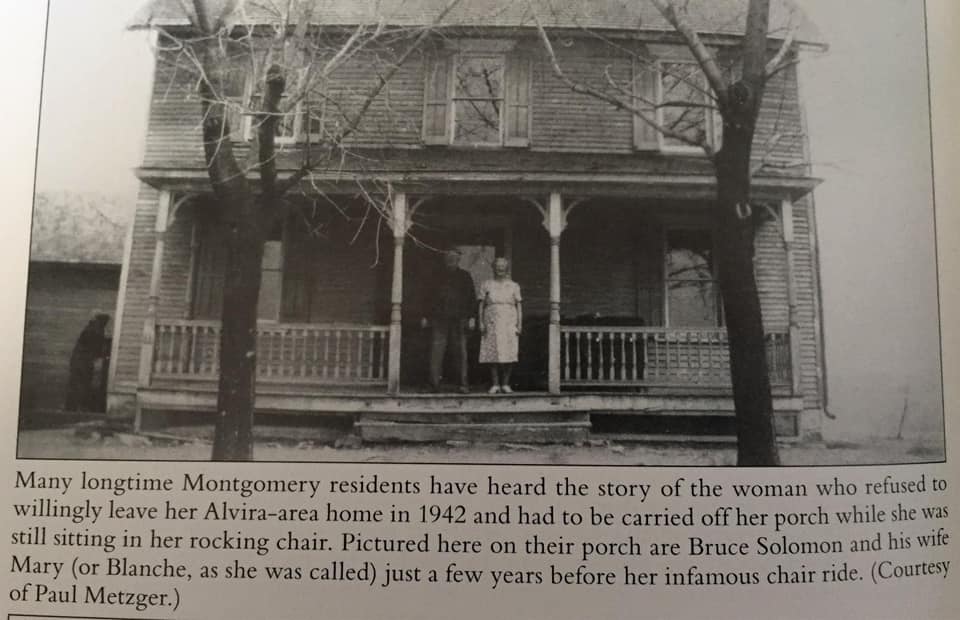

Residents were given six weeks to leave their property. Just six weeks to pack up, and move everything they owned, including livestock. Properties were purchased by the government for 30 to 35 cents on the dollar – a fraction of their actual worth, Families who resisted the low-ball offers could appeal, but the effort would be hardly worth it. It was a battle they couldn’t win, as their properties would then swiftly be taken by eminent domain.

“My great-grandmother was actually carried off her front porch and her house was torn down by bulldozers,” says historian Paul C. Metzeger.” https://www.pahomepage.com/news/hidden-history-bunkers-of-alvira/844987687

As the few remaining families left their homes and farms for the final time, it was in the shadow of smoke and flames. Huge bulldozers were in the process of leveling everything that stood, and smoke from burning rubble choked the valley.

Despite assurances, only a small handful of landowners would ever be given the opportunity to purchase their land back. There would be no place to return home to.

The POW

In less than four months, the houses, farms, and properties that comprised Alvira were obliterated.

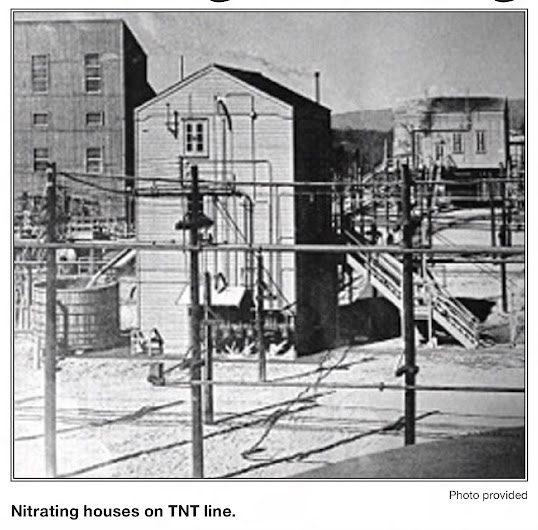

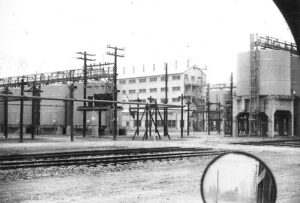

11 months of intense labor transformed the Alvira farmland into a 50-million-dollar dynamite production complex run by 3,500 workers daily.

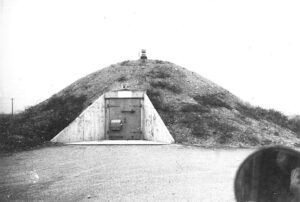

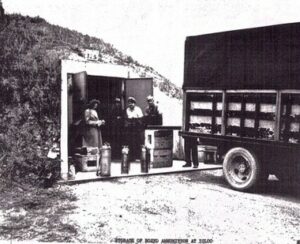

150 storage bunkers, 17 miles of railroad track, 55 miles of roads, and 300 buildings replaced what was once the town of Alvira. The bunkers were built as igloo-shaped buildings with thick walls that were designed to explode upward in the event of an accidental explosion.

In February of 1943, the Pennsylvania Ordinance Works began operations, and TNT was streaming from production lines at a monumental rate.

But a plant seemingly built to last forever, existed as a production facility for only 11 months. On April 15, 1944, the POW ceased the production of TNT and closed its doors permanently. Atomic research being conducted in the deserts of Nevada and New Mexico, code-named the “Manhattan Project” was so promising, it was clear that the days of TNT as the major engine of weaponry were ending.

There is a cruel irony here. The government moved people off their properties and demolished their homes for something that would presumably have lasted for a while.

Why Alvira?

Alvira was among 76 similar sites during World War II. Montandon escaped the same fate because it was in a floodplain.

The site was likely chosen for its proximity to the Reading Railroad, which made it easy to transport materials to the facility. It was also remote enough to keep the activities somewhat private and out of view. The tract was large enough for the 150 bunkers planned

Another consideration may have been the proximity to the Susquehanna River – which could provide the water needed for the TNT plant. A river pump house and dam were constructed on the east side of the highway, near the river.

What Happened After the POW Closed:

The POW was redesignated as the SOD – the Susquehanna Ordnance Depot – and it would function to store and maintain munitions and to transfer artillery across the nation.

On October 30, 1944, the Surplus War Property Division posted the 8,500 acres of the SOD for sale, cautioning that much of the land might be contaminated with acid, and the few remaining structures had a 5-year life expectancy at best.

Considered a burden, the SOD, still at 8,500 acres, was deactivated on December 31, 1950. By this time, most Alvirans had come to terms with their fate. But now it seemed the long-promised return of land to original owners could be realized. But this was not the case.

Another considered use for the property was a mental health facility for juvenile delinquents. The PA Game Commission wanted the property for deer propagation. In August of 1950, the Army requested the use of the land for the testing of its top secret “Ripper” technology, which were the final military tests done on the property.

In October of 1950, the Lycoming County School Board requested that 284 acres be donated for educational purposes – specifically to test crops, study conservation, and reforestation. This failed to materialize.

The Defense Department wanted to turn the site into an atomic research facility, and ironically another plan was to turn the site into the first United Nations headquarters.

The most sinister plan was to create one of six detention centers here that would house those deemed enemies of the state. There was already a makeshift minimum security prison camp located on the property for the trustees of the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary. On April 23, 1952, this detention center was activated, under the control of Colonel Guy Rexroad, who was proud to admit he had found or created space to house over 4,500 potential detainees. When asked who would be filling the beds, Rexroad replied “So far, orders are for males only, but I’m sure women will be here too… probably whole families.” Whole families, that is, of American citizens.

In 1956 The Federal Bureau of Prisons began construction on this site for what would eventually become the Allenwood Federal Prison Complex as we know it – one the largest federal prison facilities in the United States., and the largest in Pennsylvania.

Following the government’s takeover of Alivira, the only promise made to the citizens that held true

How the land was divided:

1950: 4,200 acres deeded to the US Bureau Of Prisons (This is where the Allenwood Federal Prison Complex and the landfill are now located)

1952- on: Only about 500 acres were ever sold back to their former owners at an average price of $40.80/acre.

1957: 3,018 acres were given to PA State Game Commission to form SGL252. This included the land where the bunkers are located.

1962: 220 acres sold to Lycoming County for $10,821 to construct the White Deer Golf Course

1970 -1976: 400 acres were given to the former Williamsport Community College (now known as the Pennsylvania College of Technology) for educational use.

What Remains:

Little remains to historically document the town of Alvira aside from a few photographs, deeds, diaries, receipts, and the memories of its former residents kept alive through oral tradition.

Only the Stone Church, three cemeteries, and various house foundations persist as witnesses to the physical town that once existed in this area. The Stone Church is now within the Allenwood Federal Prison and is used by the inmates. Its cemetery is well maintained and is accessible only to the family members of those interred in it. The church is only open to the public for special events such as the Christmas service.

(See photos of the Stone Church Christmas Service in 2018 here)

Nothing remains of the munitions plant or its support buildings. The only structures left are the munitions bunkers, which are slowly being swallowed up by trees and vegetation. Most are sealed shut, but some are accessible.

An interesting theory as to why residents weren’t allowed to buy their land back after the war came to light with the release of an Energy Department memo dated May 29, 1987, which revealed that between 1943 & 1944, 100,000 lbs. of radioactive uranium, 234 metal turnings, and waste from the infamous Manhattan Project were stored at the Pennsylvania Ordnance Works, specifically in bunkers 112, 120, 137 and 146.

Another document confirmed that all magazines had been emptied of the uranium by April 26, 1944, eleven days after the depot closed. It has been determined that the area is not radioactive.