Does a Lost Valley exist in Pennsylvania? An untouched patch of wilderness overflowing with wildlife that was thought to be extinct? While logic and modern technology tells us no, an old Central Pennsylvanian legend states otherwise.

Listen to Episode 5 of Pennsylvania Life, Legends, and Lore here: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/pennsylvania-life-legends-and-lore/id1673471716 or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Cultures across the world and throughout history have legends of lost lands and civilizations – Atlantis, El Dorado, Avalon, Shangri-La, Germelshausen, Brigadoon. These tales are made even more enticing as we have real life examples of islands and civilizations that just disappeared. Beringia, a submerged island that connected Asia and North America; Maui Nui, once a large island of the Hawaiian archipelago; Zealandia, a scientifically accepted continent that is now 94% submerged under the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the areas of New Zealand and New Caledonia. Lost civilizations – the Mayan Empire of Mexico and Central America, the Rapa Nui of Easter Island, the Anasazi of the American Southwest, and the lost colony of Roanoke Island in North Carolina to name a few.

The idea of a lost valley – a pristine valley, frozen in time, where extinct animals still roam, and untouched natural resources exist – has been a fascination of many writers and filmmakers. Many novels considered classics involve such lost worlds: Journey to the Center of the Earth (Jules Verne), The Lost World (Arthur Conan Doyle), and The Land That Time Forgot (Edgar Rice Burroughs).

Do lost valleys still exist in a modern world where satellite imagery shows us our surroundings in detail? The obvious answer is no, nothing is truly hidden from us in this modern age.

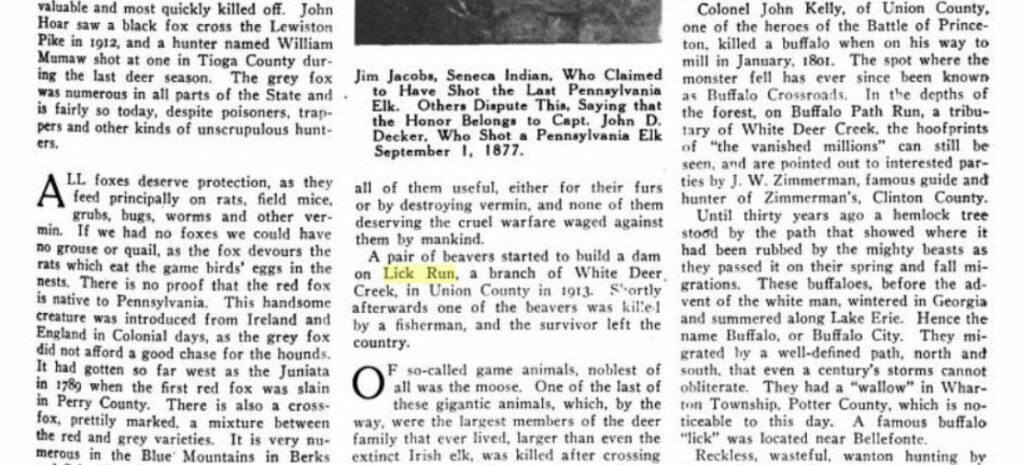

However, according to Henry Shoemaker, a lost valley does exist in the mountains of Central Pennsylvania. Recorded in South Mountain Sketches, “The Lost Valley” tells the tale of a mysterious valley filled with animals which history records as being extinct. Like many of the legends told throughout history, the ambiguous valley is not easily found – it is usually discovered accidentally, by a hiker or hunter who is lost in the mountains. According to Shoemaker, this lost valley is near Lick Run, a mountain stream which empties into White Deer Creek in Union County.

While Shoemaker’s writings are often questioned due to his tendency to embellish facts, there is something about this story that is different. Instead of immediately jumping into a highly romanticized narrative, Shoemaker begins this tale by stating he was on his third trip into the tributaries of Lick Run in his attempt to find this lost valley. While he likens the valley to the Monte Rosa lost valley legend in the Italian Alps, Shoemaker’s approach to this story makes us wonder if it may not have originated completely from his imagination or been adapted from European lore.

Shoemaker reports two reasons for his motivation to find this lost valley. The first was that a local boy named Smith had killed a beaver in one of the tributaries of Lick Run in 1913. Shoemaker wanted to see the beavers, their dam and pond for himself because this was the first beaver reported on the waters of White Deer Creek since the late 1880s.

The second item that fueled Shoemaker’s curiosity was the legend of a lost valley. The Smith boy reported that “he had looked out across a valley which teemed with every animal and bird known in that section of Pennsylvania in the olden days, the trees being filled with passenger pigeons in such numbers that they appeared blue.” He also states that the bever dam was surrounded by gum trees and two large white pines. After Smith reported his discovery, numerous explorers and hunters invaded the gap at Lick Run in quest of the mysterious valley. Despite the searches no one discovered it, or the beaver dam which was key to uncovering the location of the Lost Valley.

Shoemaker himself went in search of this mysterious valley but was only rewarded with views of the White Deer Valley from atop the mountain.

Rather than stopping there with his report, Shoemaker added to his story about the lost valley. The narrative, which Shoemaker claims came from one of his guides during his third trip to discover the valley, involved a young lady known as Hazel Hawk. Hazel was the niece of lumberman Adam Hawk, who at the time took a job with Ario Pardee, and had camps along Lick Run and White Deer Creek. Hazel and her mother arrived at her uncle’s camp after her father – Adam’s brother – was killed in a logging accident called The Great Log Jam at Lock Haven.

According to Shoemaker, Hazel was in love with a boy who lived across the mountains in White Deer Hole Valley. They had met the winter before while staying at her uncle’s camp near Fourth Gap, where Adam Hawk had a lumber job for the elder John DuBois. Unfortunately, her mother did not approve of the relationship and the two lovers met in secret, aided by Hazel’s friend “Black” Agnes Dunbar – given the nickname Black due to her very dark hair.

One autumn Sunday afternoon, Hazel set out to gather chestnuts on the ridge and while there, she was surprised by her beau. The afternoon passed quickly for the young lovers and as the sun began to set, they realized they’d tarried too long. Hazel hastily started back down the mountainside.

As shadows covered the land, Hazel lost the trail. In the misty twilight, she discovered another path which she followed believing it was the one that would lead home. The trail led her to a large beaver pond surrounded by gigantic gum trees. Hazel crossed the dam and continued down the trail. Hazel came to a large, fog obscured valley from which only the tops of pine trees protruded.

Completely lost, Hazel lay down on the ground and quickly fell asleep. When she arose the next morning, the fog had lifted and Hazel stared at the scene before her. The valley was a mixture of forests and natural meadows. From the sides waterfalls fell from the cliffs into a series of pools created by beavers and used by the wildlife of the valley. As she watched, she was amazed at the variety of animals – woodland buffalo, moose, elk, deer, panthers, wolves, and many other creatures were thriving in this remote wilderness. Birds of all sorts, including golden and bald eagles, hawks, and Carolina parrots flew among the gigantic white pines sprouting up from the valley floor.

After spending all day watching the valley from her vantage point, Hazel settled down to sleep once again. The following morning, she continued watching the wildlife in the valley below until mid-afternoon when she left to find her way home. She retraced her steps, found the beaver pond, and followed the waters until she found Lick Run. As night was beginning to cover the land once again, Hazel was discovered by searchers.

When questioned about where she had been, Hazel told the tale of the lost valley. She never wavered from it. As a result, in the days that followed her rescue, many of the lumbermen went off to find it – but with no luck.

It would be roughly 33 years later when the Smith boy brought in a beaver that he had killed along Lick Run, which would spark Shoemaker’s interest in the lost valley. We know this because Shoemaker states that the Smith boy found the beaver pond a third of a century later. If Shoemaker took any other interest in the lost valley, he never records it in any of his books.

On its own, the Lost Valley is a great tale. But within it, Shoemaker provides us with an ample number of names and dates, so naturally we had to dig deeper to see if the tale could have any validity.

We started with the Smith boy. Realistically, finding a boy with the last name Smith and no given first name would be impossible. However, considering that beavers had been essentially extinct since the 1880’s when the boy killed this beaver in 1913, it seemed plausible that an article in an area newspaper would exist to document this rare occurrence. But we found nothing – no articles about a rare beaver being killed by a boy anyway.

However, in Volume 87 of Forest and Stream published in 1917, page 123 does document that a pair of beavers was found building a dam on Lick Run in Union County in 1913, and that shortly after one of the pair was killed by a fisherman. We also found a mention in The Lock Haven Express published July 9th, 1917, that confirms the excursion taken by Henry Shoemaker and Jake Zimmerman and his crew to search for the beavers near Lick Run and the lost valley.

Additionally, we were able to verify several people and places mentioned within the story.

- The Smith boy’s father was a lumberman that was originally from the Hunter’s Run region of the South Mountains. He had a logger’s shanty that was later used as a hunting camp by Governor William C. Sproul before it was destroyed by fire in 1917.

- We could not find an article or any report from this timeframe about the hunting camp or fire, but there is a Hunter’s Run region of the South Mountains. It is a populated place in the South Mountain Range of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. Hunter’s Run is located where the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad stations were established in 1884, at a junction with the 1870 South Mountain Railroad.

- A May 27, 1936, clipping of the Altoona Tribune we found was a commentary from a reader regarding several Central Pennsylvania sites, including the Lost Valley. The correspondence mentions Governor William Sproul’s hunting camp, that it was a former Pardee lumbering operation site, and that it burnt down but gives no dates.

- The mountaineers that Henry Shoemaker traveled with existed. We found several articles that mention Jake Zimmerman and Jesse Phillips. Jake also had a grandfather who was a known guide, and tavern keeper at Tea Spring. Tea Spring is a natural spring in Pennsylvania near Little Mountain, east of Loganton and north of Forest Hill.

- White Deer Lumber Company was a major operation within Union County and operated near Hightown in the tale, which was the original name of the town of White Deer, PA. The lumber company was sold off in 1917, and the sawmill eventually followed in 1940.

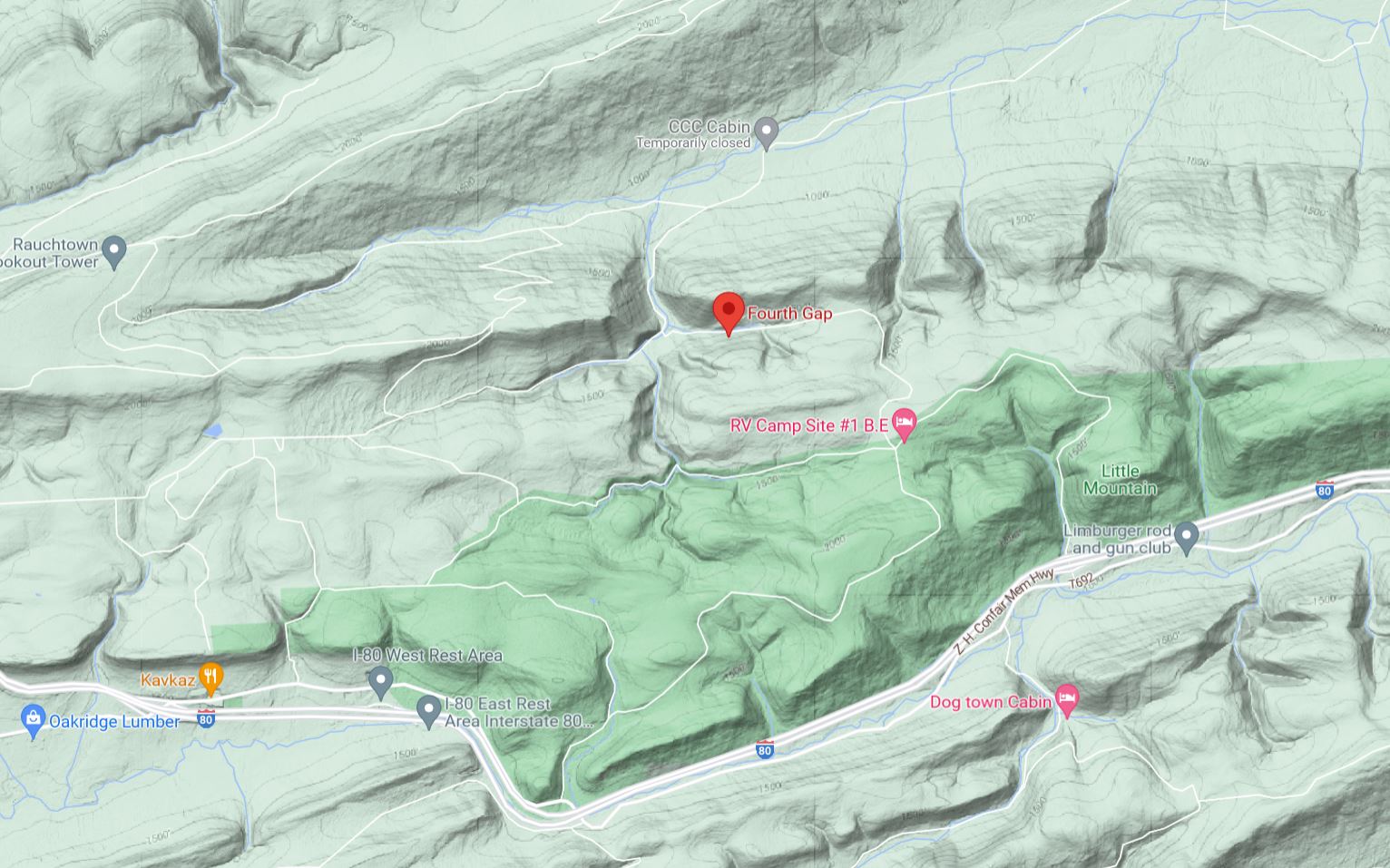

- The “Fourth Gap” where Hazel met her beau is an actual place. It’s in Washington Township, between White Deer Creek and White Deer Hole Creek – overlooking White Deer Hole Valley/White Deer Valley, which fits with the story conveyed by Shoemaker. Today, Fourth Gap Road runs through this area.

- In traveling to their new camp, Adam Hawk, his sister-in-law (who is never named), and Hazel traveled through Logansville (now Loganton) and past Sand Spring. These are actual places with Sand Springs being along Route 192. So we can assume they traveled the road that would eventually become Route 192 at least part of the way.

- Hazel described the lost valley as having waterfalls looking like Engler’s Falls in the Nippenose Valley, which is also a real place that you can visit to this day.

- The area in which Adam Hawk’s camp was located is called Lick Run Gap. It would have included Lick Run, which is an actual tributary of White Deer Creek. According to the description, the mountain that Hazel walked up on her famed walk overlooked White Hole Valley (now known as White Deer Valley). Hazel apparently could also see her lover’s home nestled at the foot of Muncy Mountain. There is a mountain region called Muncy Hills that run from the Montgomery, PA area, at the border of White Deer Valley, east past Millville, and north above Muncy.

- As described in the story, the entire length and breadth of this Lick Run Gap can be seen from the Buffalo Valley, five miles away. It is visible from the high hill beyond Youngmanstown (today Mifflinburg). The high hill could be Greenridge Rd. or the mountain behind the Forest Hill store.

- Lick Run Gap is also visible from “the pike just north of Dreisbach Church.” And from the “Chestnut Ridge” coming from New Berlin. The pike clearly describes Route 45/Old Turnpike Rd. The “Chestnut Ridge” coming from New Berlin may be Shamokin Mountain and the New Berlin Mountain Rd.

- From this description, it’s probable that Lick Run Gap is in the vicinity of Mazeppa and/or Buffalo Crossroads.

- Characters mentioned within the story existed:

- The map that Henry Shoemaker and his guides used to search for the beaver dam was provided by Lew C. Fosnot, the editor of the Watsontown Record and Star.

- In the book “The Passenger Pigeon in Pennsylvania,” an excerpt from the Record and Star on July 13, 1917, is included that details Lew C. Fosnot’s experience exploring the Pennsylvanian mountains. He describes finding wild pigeons in a remote location. This would coincide with the timeframe of Henry Shoemaker’s excursion which is described as the spring or early summer of 1917. (p. 82) https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Passenger_Pigeon_in_Pennsylvania/xopOAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=lew%20c.%20fosnot

- Ario Pardee, the boss of Adam Hawk, who was Hazel’s uncle, was a rail and lumber tycoon based out of Hazelton. Pardee founded the Lehigh Valley Railroad, however, he grew his rail company to include logging railroads along White Deer Creek, which were used by the White Deer Lumber Company and sawmills in Watsontown.

- Pardee’s woods boss Mike Courtney existed and we found several articles that document his work with Ario Pardee.

- While we couldn’t find any concrete match for Adam Hawk, we did find a potential match. In the story, Adam’s brother’s name was Hiram. Our potential match does have brothers, but none with the name Hiram.

- John DuBois the man in the story who owned the lumber company that Adam Hawk previously worked at, in the Fourth Gap where Hazel met her boyfriend, was a real person who owned a lumber company in the specified region.

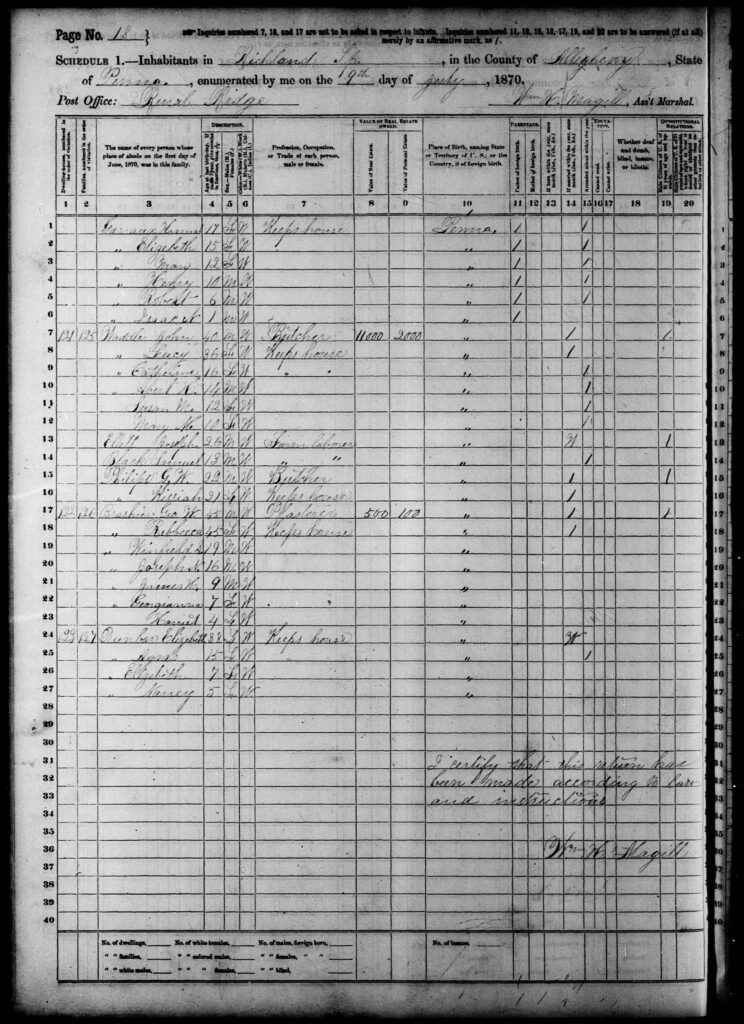

- Hazel’s friend “Black” Agnes Dunbar may have actually existed. We found one census record from 1870 for Agnes Dunbar, daughter of Elizebeth Dunbar. Elizebeth was a housekeeper, who at the time resided in Richland, PA, Lebanon County. Agnes’s birthplace is listed just as Pennsylvania circa 1855.

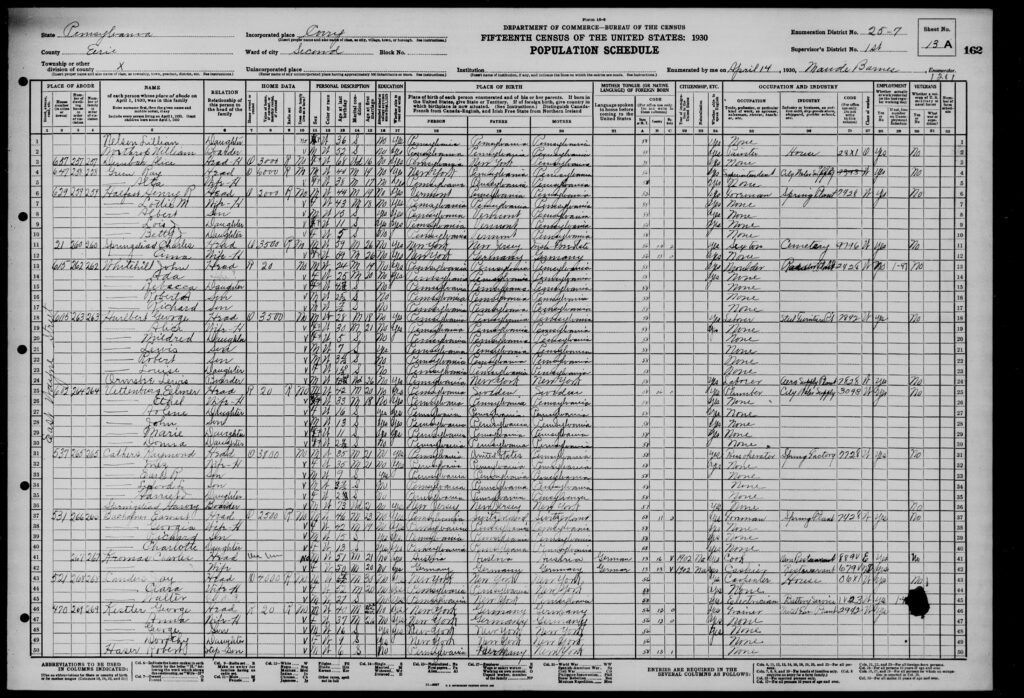

- We also found two census records for 1920 and 1930 for “Alice Dunbar, in Erie and Dauphin counties. Alice’s birthplace is listed as circa 1862 in Pennsylvania.

- The reason we began looking into the name “Alice” Dunbar is that a tale exists in both Native American legend and is also conveyed in Henry Shoemaker’s book “Allegheny Episodes,” about “Black” Alice Dunbar. Alice is a woman of similar description to Agnes in our tale, and many places and people in the “Black” Alice tale coincide with our “Lost Valley” tale.

- In the Lost Valley story, Hazel’s beau would eventually move, go to Pittsburg for law school and become a member of Congress. There are three men that could fit this bill: William Carlile Arnold, William Hepburn Armstrong, and Laird Howard Barber.

- Events in the tale occurred:

- Hiram, Hazel’s father, according to the story, died in an accident in the “Great Log Jam of Lock Haven in 1873.” The log jam was an actual event that occurred on April 22, 1874. We could not find any reports of deaths in this incident, and it seems like the severity of this event has been embellished a bit. Our potential Adam Hawk does have two brothers that passed close to the time of the log jam – although neither would have been old enough to have a family. However, the log jam was a true event that occurred in Lock Haven.

- As stated before, Volume 87 of Forest and Stream published in 1917, page 123 does document that a pair of beavers was found building a dam on Lick Run in Union County in 1913, and that shortly after one of the pair was killed by a fisherman. We also found a mention in The Lock Haven Express published July 9th, 1917, confirming the excursion taken by Henry Shoemaker and Jake Zimmerman and his crew to search for the beavers near Lick Run and the lost valley.

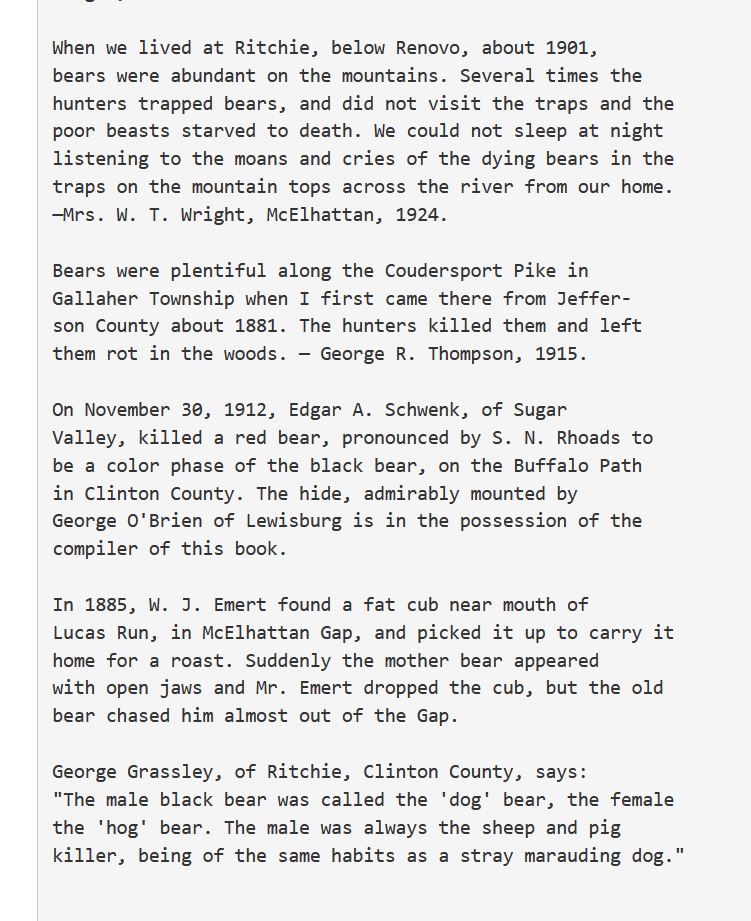

- It is mentioned more than once in this tale that people believed that a “red bear” killed by Edgar

Schwenk in the fall of 1912 came from the lost valley. We found an excerpt in a compilation called “The Wild Animals of Clinton County Pennsylvania,” documenting that on November 30th, 1912, Edgar A. Schwenck of Sugar Valley killed a red bear. Red bears were considered a potential phase of the black bear. Most likely they were what we know to be Cinnamon bears, which is a rare variation in a black bear’s fur causing it to look red.

We found several newspaper articles that refer to the Lost Valley.

- An article from the Altoona Tribune from January of 1927 relates that the Jersey Shore Herald recently published an article that in the coming spring a group from the Isaak Walton League and the Pennsylvania Alpine Club would be making a renewed effort to locate the Lost Valley. The group stated that the forestry charts showed a small un-mapped, un-surveyed area in that region. We could not find the archives of the Jersey Shore Herald.

- An article from the Altoona Tribune on February 8, 1927, discussed the letters that poured in from readers regarding the Lost Valley. Some of the accounts confirmed the unmapped region near Lick Run and how compasses and other magnetic devices go haywire in the region.

- An April 25, 1936 article in the Altoona Tribune documents a trip from the Pennsylvania Alpine Club to find the Lost Valley, which was unsuccessful. It also relates an account from one of Jake Zimmerman’s Hunting buddies (who goes unnamed), who was lucky enough to stumble into the Lost Valley. He claims that the valley lies near a glen called Steep Bank Hollow, which leads down to a point down behind Wisetown (Alvira). The Steep Bank Hollow begins at Indian Grave Spring. It also documents how aircraft mechanics go wacky when flying over the area.

- A May 27, 1936 clipping of the Altoona Tribune we found was correspondence to the newspaper about three legendary places in PA including the Lost Valley from a reader of the paper. The correspondent relays a story where Ario Pardee did not return to his camp after taking an afternoon walk. The men at his camp feared he had stumbled upon the Lost Valley and would not be able to find his way out and be lost forever. A few of Pardee’s friends eventually found him discussing the Bible with a young woman who lived isolated in the woods.

- This same article mentions Governor William Sproul’s hunting camp, that it was a former Pardee lumbering operation site, and that it burnt down.

- An Article from the Atloona Tribune on October 6, 1938, documents that the lost valley has been seen from a distance when flying over the White Deer region of PA. The introduction of airplanes provided a completely new avenue to view the valley. It is noted that there was a distinct color change in the vegetation, and different species of trees present. Apparently, aviators at this time professed that their planes compasses and devices would go out of whack if they got too close to the lost valley. However, once landed, if they tried to discover the valley on foot, even using the exact coordinates that they knew should take them there, the valley would disappear into mist or mirage caused by broken sunlight through the trees.

- This same article also details how one can only visit the valley once – those who have found it, have never found it again. It also stated that Jake Zimmerman did eventually find the lost valley, but in his over 75 years of exploring the mountains of that region, never discovered it again.

- One clipping from the Altoona Tribune November 15,1938 was an interview with Jake Zimmerman prior to his 90th birthday that detailed his adventures. Included in this list was his attempts to find the Lost Valley, making note that the ancient pines that guarded the path to the Lost Valley are gone. Several familiar names were also noted from the story – Ario Pardee, Jesse Phillips, Mike Courtney, and Lew C. Fosnot.

- An article in the June 2, 1939 edition of the Altoona Tribune quotes Zimmerman saying that due to the plundering of the wilderness by modern industrial society, that he believes the “Lost Valley is the sole baffling mystery left of the grand rugged region” he loved because time could not touch it.

- An October 2, 1940, article documents that Jake Zimmerman, Jesse Phillips, and Henry Shoemaker did eventually find the valley in 1921. It also states the valley can be found in “Zimmerman country” where four counties meet (Centre, Clinton, Lycoming and Union).

- An article from May 18, 1946, relays an incident around 1889 where a herd of horses were out to pasture at Lick Run, when they were chased off by a panther. All the horses were recovered except for a solid black yearling. People expected that it had fallen prey to the panther, but no bones were found. In 1910, 21 years later, an old horse, white with age, was shot in the region – mistaken for a white deer – by one of Governor William C. Sproul’s hunting party. No one had lost a horse in the area, nor was it ever determined where the horse came from.

- A May 30, 1947, article in the Altoona Tribune reports an old Native American legend of the lost valley. According to the legend, the valley can be found only once in a lifetime, which is why it has stood through the ages. It is a hidden sanctuary from the white man’s destruction of wildlife.

- An Altoona Tribune article from February 8, 1948, details the disappearance/possible kidnapping of a girl from the Lick Run region. Despite ongoing searches, no trace of her, or the men posing as friends of her family were found. It was widely assumed that the group stumbled upon the lost valley and was lost forever as there’s no sense of time within the valley.

In all these articles, the lost valley is discussed as if it is assumed to be a real place. No one is questioning its existence, which is interesting. It’s very possible that articles from other papers existed and includes reports on the lost valley or the other events within this story, but many of the newspaper archives from that time period are incomplete, and we didn’t find anything else in our search.

Additional Thoughts:

There is an old Pennsylvanian Indian legend regarding the Native American Queen Nita – Nee that includes a lost valley. While there are many versions of this tale, one has her losing her love in a battle with the North Wind. She covered her love’s body with a mound and laid on it in her grief. When the North wind returned, she faced it, raising the mound up to protect her people from the storm, and in the process being enveloped by the mound. The mountain she created would protect her people in a pristine valley for centuries to come, as long as her memory is kept. Some say that this valley is now what we know to be State College, but other versions claim that it is forever hidden, still protecting Nita- Nee’s people within.

One question we had during the research is that if Hazel’s camp was at the base of Lick Run, if you look at a map, it makes more sense to have traveled straight across from Loganton through the Sugar Valley Narrows to Lick Run, rather than going over the mountain to 192 and then back up to Lick Run. Maybe this travel detail was a mistake or embellished? An 1856 map of Union County shows a “White Deer Turnpike” existed in this area that would allow travel to Lick Run more directly, but an article from the Altoona Tribune on November 15, 1938, relating Jake Zimmerman’s life adventures describes this road as wild and suited for travel only by those who knew it well.

That being said, enough factual details exist to make us wonder if there could be any truth to this legend.

How many places in our area are called “lost” or “hidden” valley? Is this some unconscious realization of this legend in modern day? Is this a watering down of greater legend? We live amongst so many mountains and valleys that it’s very easy to assume something called hidden or lost valley is just a cliché labeling that attracts tourists. Perhaps it’s actually connected to something larger?

Does a lost valley exist in the mountains of central Pennsylvania? While logic screams “No,” many of us would like to believe a valley untouched by humans still exists. However, maybe like the mythical Brigadoon, of Scottish folklore that only appears every 100 years, our lost valley rests hidden in time and space and only when the stars align and the fog lifts can it be seen by those lost in the mountains.

Schwenk in the fall of 1912 came from the lost valley. We found an excerpt in a compilation called “The Wild Animals of Clinton County Pennsylvania,” documenting that on November 30th, 1912, Edgar A. Schwenck of Sugar Valley killed a red bear. Red bears were considered a potential phase of the black bear. Most likely they were what we know to be Cinnamon bears, which is a rare variation in a black bear’s fur causing it to look red.

Schwenk in the fall of 1912 came from the lost valley. We found an excerpt in a compilation called “The Wild Animals of Clinton County Pennsylvania,” documenting that on November 30th, 1912, Edgar A. Schwenck of Sugar Valley killed a red bear. Red bears were considered a potential phase of the black bear. Most likely they were what we know to be Cinnamon bears, which is a rare variation in a black bear’s fur causing it to look red.